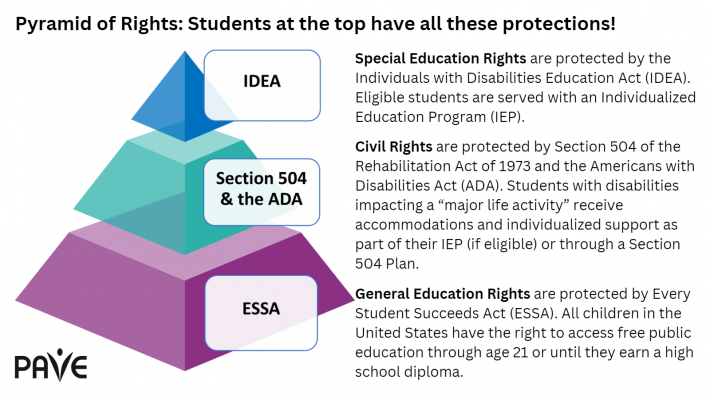

When a student is struggling in school and may have a disability, families can request a formal evaluation to explore eligibility for special education services. The process includes submitting a written referral, participating in a team-based assessment, and using the results to guide individualized supports. Even if a student doesn’t qualify for an IEP, other protections and accommodations may still be available.

A Brief Overview

- Special Education is provided through the Individualized Education Program (IEP) for students with qualifying disabilities.

- Anyone with knowledge of a student’s needs can make a referral for evaluation.

- If a student is struggling and has a known or suspected disability, the school must evaluate to determine eligibility for special education.

- Referrals must be made in writing, and schools must support families in removing barriers to this process, including providing translation and interpretation.

- To qualify for an IEP, a student must meet three criteria: have a disability, experience adverse educational impact, and need Specially Designed Instruction (SDI).

- Families are active participants in the evaluation and IEP development process and may request revisions to evaluation summaries and IEP statements.

- Eligibility is determined based on how a disability affects learning, not solely on a medical diagnosis, and must fit one of 14 federally recognized categories.

- Schools follow specific timelines for responding to referrals, completing evaluations, and developing IEPs.

- PAVE provides Sample Letters to Support Families in Their Advocacy, including a Sample Letter to Request an Evaluation.

Introduction

When a student is struggling in school and may have a disability, families have the right to ask for an evaluation to better understand their child’s needs. This process helps identify learning challenges and guides decisions about supports that can make school more accessible. Starting with a referral for evaluation, families and schools can work together to identify what a student needs to thrive with individually tailored school-based supports.

Who Can Make the Referral?

Anyone with knowledge of a student’s learning or developmental needs can make a referral for special education evaluation. This includes parents, guardians, family members, teachers, school staff, counselors, early learning providers, and even community members. Referrals can be made for students ages 3–21 who are suspected of having a disability and may need special education services.

School districts are required to actively seek out and evaluate students who may need support. This responsibility is called Child Find, and it is part of the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Districts must have procedures in place to locate, identify, and evaluate students, including those who are unhoused, in foster care, highly mobile, or attending private schools within district boundaries.

Removing the Barriers to Evaluation

Schools must support individuals who are unable to write by helping them complete the referral in another format. This includes offering assistance in drafting the referral or providing alternative methods such as verbal requests or translated forms. The goal is to remove barriers that might prevent a family from initiating the evaluation process.

Schools are legally required to provide evaluation materials and meeting support in the family’s native language or preferred mode of communication. This includes oral translation, sign language interpretation, Braille, or other formats when written language is not used. During the evaluation process, districts must ensure that parents understand all documents and decisions, and must document that translation or interpretation was provided. For example, prior written notice must be translated orally or by other means, and the district must keep written evidence that the parent understood the content. These protections are outlined in the statewide Procedural Safeguards developed by the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI).

Appropriate Evaluation

The IDEA requires schools to use “technically sound” instruments in evaluation. Generally, that means the tests are evidence-based as valid and reliable, and the school recruits qualified personnel to administer the tests. A single assessment tool, such as an Intelligence Quotient (IQ) test, is not enough to determine eligibility for special education services. Instead, schools must conduct a comprehensive, unbiased evaluation using multiple methods to understand a student’s unique educational needs. This process involves a team approach and includes parents or guardians as active participants. The results help guide decisions about how best to support the student’s learning.

Evaluation Criteria as a 3-part Process

Not every student who has a disability and receives an evaluation will qualify for an IEP. The school district’s evaluation asks 3 primary questions in each area of learning that is evaluated:

- Does the student have a disability?

- Does the disability adversely impact education?

- Does the student need Specially Designed Instruction (SDI)?

If the answer to all three questions is Yes, the student qualifies for an IEP.

Family Role in Evaluation

Keep in mind that a student does not need to meet all three criteria to be evaluated. Under the Child Find Mandate of IDEA, the school district must evaluate a child if there is a known or suspected disability that may have significant impact on learning.

Families are active participants in the evaluation process. After the evaluation is reviewed, the IEP team meets to talk about how to build a program to meet the needs that were identified in the evaluation. Key findings are summarized in the Adverse Educational Impact Statement, which guides the rest of the IEP. Additional findings become part of the present levels statement, which are matched with IEP goal setting and progress monitoring.

Read the Adverse Educational Impact Statement carefully to make sure it captures the most important concerns. The rest of the IEP is responsible to serve the needs identified in this statement. Families can request changes to this statement at IEP meetings. PAVE’s article, Advocacy Tips for Parents, provides information to help families prepare for and participate in meetings.

From Evaluation Results to IEP

Information, or data, collected during the evaluation is essential for developing the IEP. One of the most important outcomes of the evaluation is determining whether the student needs Specially Designed Instruction (SDI), which is the “special” in special education. The evaluation determines whether SDI is needed to help a student overcome barriers and access learning in ways that work best for them.

SDI is tailored instruction that helps a student overcome barriers caused by a disability and access learning in ways that work best for them. This may include changes in content, teaching strategies, or learning environments. For example, SDI might involve breaking tasks into smaller steps, using visual supports, or providing extra time for assignments. These supports are designed to help the student make meaningful progress in school.

Understanding how SDI works can help families participate more fully in IEP development. Asking questions about SDI can lead to more effective planning and collaboration. For example:

- What specific instruction will be provided?

- Who will deliver it?

- How will progress be measured?

These questions can guide meaningful conversations during IEP meetings and ensure that the IEP reflects the student’s strengths, challenges, and learning needs.

To learn more, watch PAVE’s three-part video series: Student Rights, IEP, Section 504, and More.

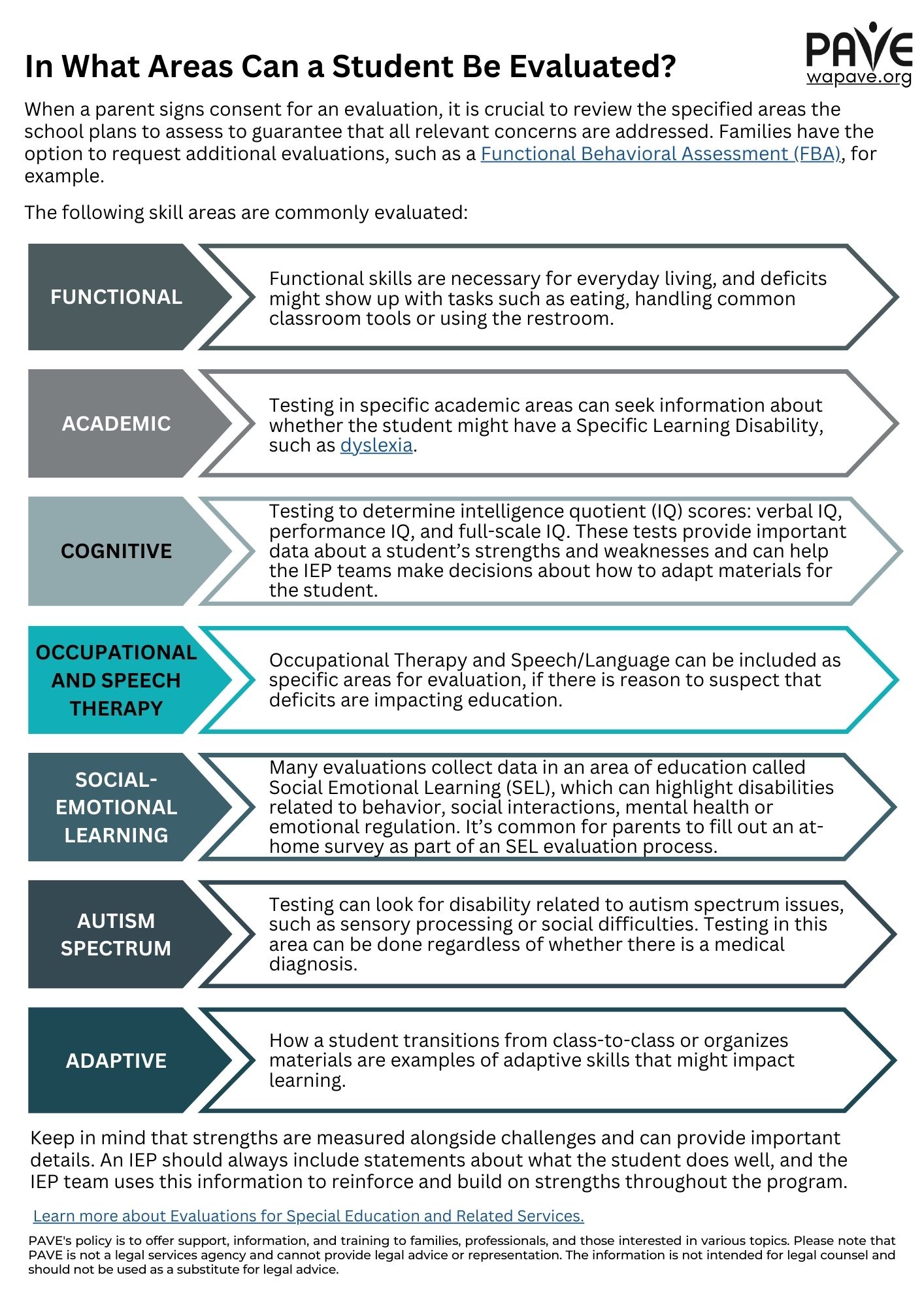

In What Areas Can a Student Be Evaluated?

When a parent signs consent for an evaluation, looking through the list of areas the school intends to evaluate is important to ensure that all concerning areas are included. Families can request additional areas to include in the evaluation, including a Functional Behavioral Assessment, for example.

Keep in mind that strengths are measured alongside challenges and can provide important details. An IEP should always include statements about what the student does well, and the IEP team uses this information to reinforce and build on strengths throughout the program.

Below is an infographic showing skill areas that are commonly evaluated:

Download In What Areas Can a Student Be Evaluated?:

English | Chinese (Simplified) 中文 (Zhōngwén) | Korean 한국어 (Hangugeo) | Russian Русский (Russkiy) | Somali Soomaali | Spanish Español | Tagalog | Ukrainian українська | Vietnamese Tiếng Việt

Eligibility Categories for Special Education

Once a student’s evaluation confirms a disability that impacts learning, the next step is to determine whether the disability fits one of 14 federally recognized categories. These categories are outlined in Washington’s Administrative Code (WAC 392-172A-01035):

- Autism

- Emotional Disturbance

- Multiple Disabilities

- Specific Learning Disability

- Visual Impairment / Blindness

- Deaf-Blindness

- Hearing Impairment

- Orthopedic Impairment

- Speech/Language Impairment

- Developmental Delay (ages 0-8)

- Deafness

- Intellectual Disability

- Other Health Impairment

- Traumatic Brain Injury

These categories are intentionally broad to reflect the diverse ways disabilities can affect learning. The IEP team may discuss which category best fits the student’s unique situation. While a medical diagnosis can help inform the process, eligibility is determined by how the disability impacts the student’s education. This impact can be assessed with or without a formal diagnosis.

There is no such thing as a “behavior IEP” or an “academic IEP.” Once a student qualifies, the school is responsible for addressing all identified areas of need. The IEP is personalized to include programming, services, and placement designed to support the whole child.

In Washington State, children through age 9 may be eligible for services under the category of Developmental Delay. Full definitions for each category are available in WAC 392-172A-01035 and are also reproduced in this PAVE article: Washington Special Education Categories.

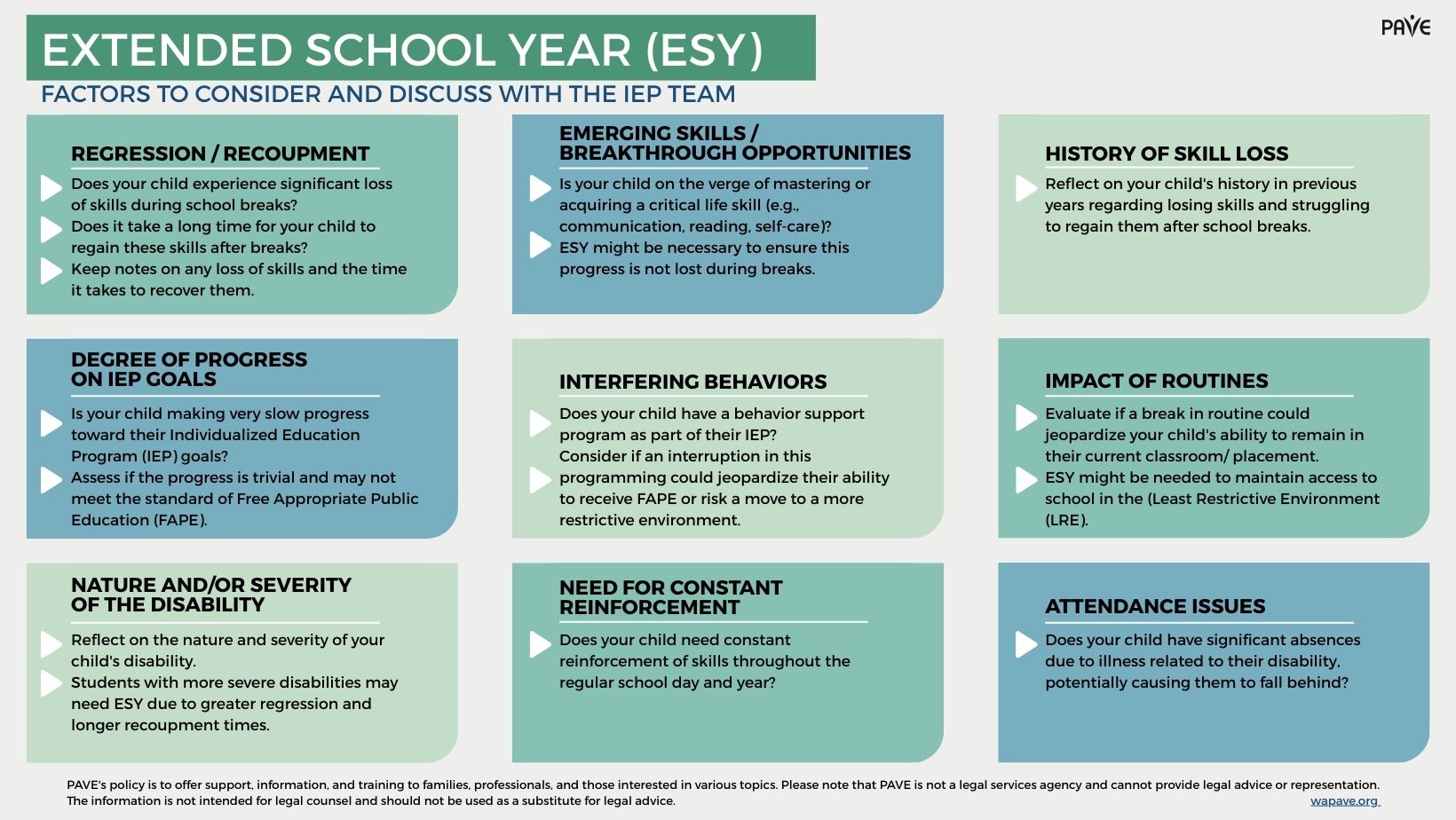

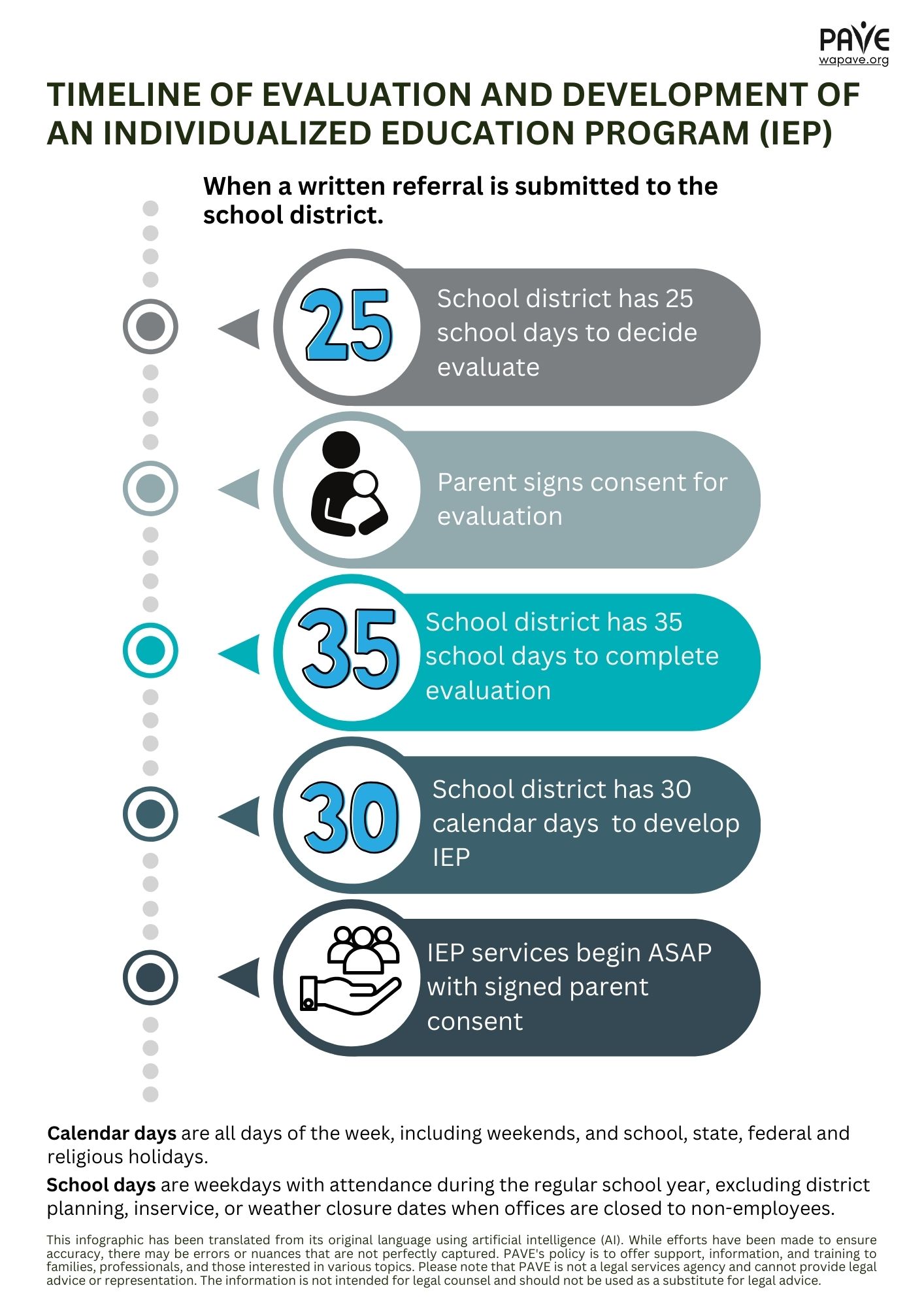

Timeline of Evaluation and Development of an IEP

The school follows specific deadlines for an evaluation process. They have 25 school days to respond to the referral in writing. If they proceed with the evaluation they have 35 schools days to complete the assessment. For an eligible student, an IEP must be developed within 30 calendar days.

Track your student’s progress from the point of referral for evaluation to the development of the IEP with the infographic below.

Download the Timeline of Evaluation and Development of an IEP:

English | Chinese (Simplified) 中文 (Zhōngwén) | Korean 한국어 (Hangugeo) | Russian Русский (Russkiy) | Somali Soomaali | Spanish Español | Tagalog | Ukrainian українська | Vietnamese Tiếng Việt

Sample Letter to Request an Evaluation

Washington law requires that referrals for special education evaluation be made in writing. If a verbal request was previously denied, start again with a formal written letter sent by email, certified mail, or delivered in person.

OSPI provides a downloadable referral form on its Making a Referral for Special Education page. The person making the referral can use this form or any other written format that clearly communicates the request to evaluate.

Address the referral to the district special education director or program coordinator, and include an administrator at the student’s school. Be sure to include the student’s full name and birthdate, a clear statement requesting evaluation in all areas of suspected disability, and specific concerns. Supporting documents or letters from doctors, therapists or other providers may be attached. Include complete contact information and a statement that the parent or guardian is prepared to sign consent for the evaluation to begin.

Download the Sample Letter to Request an Evaluation:

English | Chinese (Simplified) 中文 (Zhōngwén) | Korean 한국어 (Hangugeo) | Russian Русский (Russkiy) | Somali Soomaali | Spanish Español | Tagalog | Ukrainian українська | Vietnamese Tiếng Việt

Options When Families and Schools Disagree

Families can ask school staff to explain their decisions in writing. If a parent or guardian disagrees with something the school decides, they have rights to informal and formal dispute resolution options that are protected by the IDEA. Schools must provide a document called procedural safeguards, which outlines these options and explains the rights of both students and families. PAVE continues this topic in an article: Evaluations Part 2: Next Steps if the School Says ‘No.’

Eligibility for Section 504 Protections

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 is a federal civil rights law that helps protect students with disabilities from discrimination in schools that receive federal funding. It applies to individuals whose disabilities significantly affect major life activities—such as learning, breathing, walking, or concentrating. Because the law is broadly written, it can apply to a wide range of conditions and circumstances.

Students who receive services through an IEP also benefit from protections under Section 504, which are built into the IEP process. In some cases, students who don’t qualify for an IEP may still be eligible for support through a Section 504 Plan.

Protections against bullying and discriminatory discipline are aspects of Section 504. PAVE provides articles about Bullying at School: Resources and the Rights of Students with Special needs and What Parents Need to Know when Disability Impacts Behavior and Discipline at School.

Learn More

PAVE provides downloadable toolkits ready for you, including Where to Begin When a Student Needs Help. For the full list of toolkits, type “toolkit” in the search bar at the top of this page.

Click on Get Support at the top of this page to submit a Support Request and receive individually tailored support, training, information, and resources.